Links

Center

Field

Love

of the Game

Timeline

Today

CF

Media

E-mail |

The summer of 1997 in sports

BY NATHAN BIERMA

Winner of the 1998 Grand Rapids Christian High School Fine Arts Award for Narrative Essay

At the time, of course,

it didn't seem the least bit ironic

that Van Halen's "Standing On

Top Of The World" was among the

songs blaring over the Joe Louis

Arena loudspeaker in Detroit

that warm June night.

After all, the Detroit Red Wings had just

won the Stanley Cup for

the first time in 42 years, and the

songs' title appropriately

described the teams' status after it

steamrolled

over Philadelphia for the championship. The subtle steamrolled

over Philadelphia for the championship. The subtle

irony came in a line from

that song, one that no one could know

would prove hauntingly prophetic,

"We'll be standing on top of

the world, for a little

while." No one knew just how little that

blessed while would be--that

in fact the elation of victory would

be deflated only six days

later.

But at the time no one thought

twice about it, and why

should they have?

The last time the Red Wings won the Stanley

Cup, the most treasured

trophy in sports, Eisenhower was in the

White House, the Dodgers

were in Brooklyn, and rock n' roll was

in its infancy. Of

course, this championship drought was

supposed to have emphatically

ended one or two years ago, when

the Red Wings appeared to

have a more formidable team. But now

no one seemed to mind; in

fact, the failures of recent years made

1955 seem even longer ago.

Hockey tradition has it that

the captain of the winning team

first receives the Stanley

Cup, and this year no Red Wing

deserved this honor more

than captain Steve Yzerman. The city of

Detroit is known for its

quiet superstars, housing Barry Sanders

and Grant Hill, but before

either of them came to the Motor City,

there was Steve Yzerman.

Yzerman

joined the Wings 13 years ago, the season before the Yzerman

joined the Wings 13 years ago, the season before the

Tigers won baseball's World

Series, Detroit's last championship.

That's the longest stint

with one team of any active hockey

player, nearly twice as

long as any other Red Wing. And playing

for a perennial power in

hockey has not been easy, not when such

a power is rendered pathetic

year in the playoffs each year.

There had been trade rumors

and rifts with coaches, but the

playoff losses were the

worst--in this decade two first round

upsets, an Stanley Cup Finals

sweep at the hands of underdog New

Jersey, and a bouncing out

in the conference finals last year

after setting a record for

most regular season wins ever.

Through it all Yzerman has

maintained a quiet dignity, polite and

straightforward, avoiding

the ego-driven antics of other

dissatisfied stars.

So when Steve Yzerman hoisted

the 35-pound Stanley Cup above

his head--"heavy, but kind

of light, too," coach Scotty Bowman

would say--no one was expecting

the bug-eyed grins and wild

shaking of the trophy of

previous winning captains, just an

overwhelming sensation of

satisfaction, years and tears in the

coming. You didn't

have to be a Detroit Red Wings fan, you

didn't have to be a hockey

fan, to know that this is what sports

is all about, this is what

kids still dream of when they go to

bed at night, this is the

kind of rare moment that maintains an

sense of purity amid a senseless

and money-crazed sports world.

Rivaling Yzerman's stoicism

if not his desperation was

Scotty Bowman, the uncharacteristic,

sometimes aloof, yet highly

successful coach of the

Red Wings. While Yzerman sought his

first Stanley Cup, Bowman

was in search of his eighth, the one

that would make him the

first coach to win with three different

teams. But despite

the unprecedented history he wrote in years

past, he knew this chapter

would be a defining one, that he would

have to win in Detroit to

prove that he was not just a legend; he

was still a good hockey

coach. Many doubted this as Detroit

fumbled golden playoff opportunities

and a handful of Red Wings

regulars were traded, alienated

by Bowman in a confrontation of

personalities. Even

as Bowman was wrapping up his 1,000th career

victory this season, the

first and probably last ever to reach

that mark, the questions

remained.

But the person who probably

cared least was Bowman himself.

The phrase laid back doesn't

do justice to his perpetual

nonchalance. One sportswriter

once described former Toronto Blue

Jays manager Cito Gaston

as auditioning for a spot on Mount

Rushmore; Bowman provided

stiff (literally) competition. Maybe

he had just seen too many

games over the course of his great

career to be fazed by any

win or loss--indeed, his face provided

a poor scoreboard.

After an especially thrilling game-winning

overtime goal in the second

round of this year's playoffs, an

assistant coach tried to

celebrate, raising his arms and

eyebrows, only to turn to

the staid Bowman, seemingly preoccupied

with postgame transportation

arrangements, in any event unmoved

by the bedlam unfolding

around him.

So the most unlikely celebration

at Joe Louis Arena that

championship night in June

came in the form of Bowman, lacing up

ice skates after the game

and joining his players for a victory

lap on the ice, wearing

a broad smile most assumed he had long

packed away in an attic

somewhere--unusual for any coach, but

especially the indifferent

Bowman. This was his eighth, but he

carried it as though it

were as new to him as it was to the long-

suffering fans of Detroit.

They all hoisted the Cup

before the night was over--Brendan

Shanahan, brought in at

the start of the season to provide much-

needed brawn; Sergei Federov,

this year silencing critics of his

previous playoff disappearances;

Darren McCarty, who scored the

game-winning goal in the

decisive game in highlight reel fashion

despite his preference for

fighting, not offense.

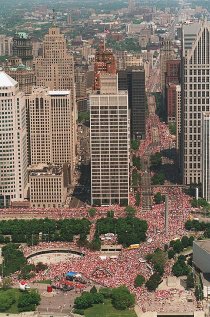

They

celebrated that night; then, two days later, they They

celebrated that night; then, two days later, they

celebrated all over again,

this time in downtown Detroit, bathed

in the afternoon sun.

Parents pulled their kids from school,

eyeing a more memorable

education that day, and crowds swelled to

estimates of one million

people. Somewhere amid the throbbing

throng was the vehicle housing

Steve Yzerman and the Stanley Cup,

which he periodically raised

for the jubilant masses. On this

day a theme transcending

sports was unmistakable--this is more

than a hockey club; it's

the heartbeat of an entire city. While

unity for urban betterment

seems utopian in such a diverse, vast

metropolitan area, the simplicity

of sports accomplishes what the

seemingly more meaningful

cannot--bring thousands of people

together to rally around

one common cause. And nothing magnetizes

them like a championship,

especially one decades in the making.

This urban unity and identity

through sports is largely lost

in the American sports scene

today. Stars come and go like

unsuccessful politicians,

tossed around by the towering waves of

millions of dollars.

Now most athletes fall short of the once

effortless accomplishment

of heroism; they're only expensive

icons on whom a jersey with

a city's name seems inappropriate for

its temporary status and

high price. That's the difference

Detroit realized that day--Yzerman,

captain of the only team he's

ever played for, and played

for over a decade, actually worthy to

be at the center of all

this attention, the epitome of what an

athlete should be these

days, and the rest of the team, assembled

not primarily by money but

by the consuming cause of finally

winning a championship for

the city affectionately known as

"Hockeytown."

But if the elation of victory

transcended sports, so did the

stunning tragedy of days

later. They had waited 42 years; now

the celebration would quiet

down after not even one week. The

teams two Russian defensemen,

Vladmir Konstantinov and Slava

Fetisov, left a team gathering

with team trainer Sergei

Mnatsakanov, in one of the

limos arranged by the team in

anticipation of alcohol

consumption by the players. Taking this

safety precaution, however,

placed the players in another form of

danger--the driver for these

three had his license revoked a year

ago after 11 traffic violations,

including driving under the

influence, in just six years.

Shortly after 9:00 that Friday

night he swerved off the

road and collided with a tree,

reportedly after falling

asleep at the wheel. Konstantinov and

Mnatsakanov were left unconscious,

Fetisov injured but released

from the hospital days later.

No one ushered any of the

Red Wings from the intensive care

unit despite a family-only

policy--the team had already seemed a

family, now more than ever.

It was the captain Yzerman, no more

immersed in celebration,

now subdued by the severity of this

event, asking in a faltering

voice for the prayers of Detroit for

Konstantinov and Mnatsakanov,

both in a coma.

If the mood of Detroit had

seemed something surpassing

sports after the thrilling

Stanley Cup win, now it was equally

extraordinary, though drastically

different. Again events

rendered petty the supposed

importance of hockey, a game played,

as now lives lived hung

in the balance. It no longer mattered

that Konstantinov was a

star defenseman, a finalist for the

Norris Trophy as best blueliner,

an intense player other teams

accused of playing dirty,

seen by his team as essential. The ice

was a million miles away,

as the sport of life took center stage,

crippling player and trainer

with equal regard. Hockey seemed a

game again, the championship

drained of its sweetness, now a

distant memory.

Fetisov will probably make

a full recovery with relative

ease; Konstantinov and Mnatsakanov

gradually regain consciousness

and ability but remain in

serious condition. Continuation of

their careers is unlikely

but not even in the forefront of

consideration by the doctors

or the team--the only concern is for

them to walk again and live

with as much normalcy as possible.

So in just one week the city

of Detroit and its team rode a

roller coaster covering

the peak of sports accomplishment and the

impeachment of its importance.

Meanwhile the Red Wings will

maintain their champion

status at least until next June; their

names will be inscribed

on the Stanley Cup with all the champions

of years past.  But

they will be somewhat distracted next year, But

they will be somewhat distracted next year,

and healthily so.

After a journey of 42 years in which the goal

of winning seemed of unmatched

importance, a tragedy shaped the

focus of a city and an out-of-proportion

sports world. It is an

opponent that cannot be

defeated as other hockey teams by stellar

play on an expanse of ice.

Now the song played on championship

night hits home; "standing

on top of the world" is no longer a

chief concern, not with

the abrupt end of such "a little while."

Now the Stanley Cup, sought

religiously for so long, is just a

trophy again.

The

sports world is too often an inattentive student in the The

sports world is too often an inattentive student in the

classroom of life, gazing

out the window at irrelevant fun and

games or the pretty girl

of pecuniary prosperity obstructing the

teacher. If it bypasses

this lesson its graduation to sensible

priorities looms as distant

as ever. Detroit has learned,

unwillingly and painfully.

It hopes its being shaken to the core

eliminates the need for

others to learn with such debilitating

drama, but it knows with

equal conviction that this lesson in

life disregards any student's

volition.

The Summer of 1997 in Sports

Hockey: Triumph and Tragedy

Basketball:

One for the ages, again

Boxing:

Dismemberment and disgrace

Golf:

Two tough to take |

steamrolled

over Philadelphia for the championship. The subtle

steamrolled

over Philadelphia for the championship. The subtle